Ask anyone within the apologencia of the financial services

industry why bankers are paid so much and the stock answer you will receive is

that in a knowledge-based world, talent is the key source of competitive

advantage; and so banks pay the market rate to retain talent and remain

competitive. But with banks across North America and Europe still on central

bank life-support, how well does this argument stack up five years on from the

2007 crash?

The apologists’ answer is to emphasise recent hardships and

the perennial threat of talent flight. In terms of hardship, many

emphasise that talent have lost their jobs and have lower bonuses (than

last year). Others

argue that the shift towards non-cash, deferred bonuses has robbed talent of

its deserved payout because an individual’s pay is now more reliant on the

performance of their company’s stock, over which any one unit of talent has

little control. The 50% tax rate on high earners also pushed talent to

the brink, so that further attacks on their pay could potentially lead to talent

flight to competing sectors in Switzerland, France, Germany, Hong Kong and

Singapore. And that is some threat, if we are to believe Nick

Clegg’s recent assertion that without the tax paid by financial services during

the 2000s, there would be little public sector job growth outside of London (though

we shouldn’t because it is patently incorrect).

For all the made-for-TV, strategic emotion around the loss

of banking talent, are we in danger of becoming paralyzed by the fear of losing

something that perhaps wasn’t really there in the first place? Answering this

question really depends on what we mean by ‘talent’ and how we understand the

relation between skill, performance and reward. Is talent something you have,

or something you demonstrate? And is reward something that reflects your

achievements, or reflects the context within which your achievements take

place? These questions are all the more pertinent at a time when billions,

perhaps trillions, of central bank money is being poured into the UK’s

financial institutions, yet so much still ends up in the pockets of a very

select few. By what metrics might we know ‘talent’? By what achievements might

we award it its name? Perhaps we might gain some insight by briefly looking at

the particular history of the term.

The etymology of the noun ‘talent’ is interesting in its own

right. In its first meaning, dating back to the ninth century, ‘a talent’ was an

ancient weight or a money of account widely used by the Assyrians, Babylonians,

Greeks, Romans, and others so that, for example, a Babylonian silver talent was

equal to 3000 shekels. By the early 17th Century the themes of

measurement, value and field of application were transposed to the realm of

human endeavour: ‘talent’ defined an aptitude for something expressed or implied. Talent was given its name only

in a particular field, where superior skills could be assessed, valued and

valorised.

But like many English words and phrases with such history,

there is blur, overlap and polysemy as the ebb and flow of language carves new

distributaries which divert from the main stem. ‘Talent’ again around the 17th

Century also took on an additional meaning, one with a quasi-spiritual accent.

This second ‘talent’ was used to describe a divinely entrusted power or ability

of mind or body; one that required space and nurturing to flourish. This talent

had no referable field of application, this talent was mercurial and

precocious, embodied and thus inimitable, but also boundless in its

application.

It is this latter ‘talent’ that is now summonsed in the defence

of bankers pay. It is an abstract talent that is not only portable but - like

fairy dust – has the ability to transform whatever or whomever it touches: it

is dextrous and dynamic so that it can be applied to any industry, any field. In

a knowledge-based economy, this is the kind of talent that all organisations

want, and are so desperate to pay for.

This quasi-spiritual definition is particularly convenient

for the apologists of finance. It allows all economic questions to be framed in

terms of the need to provide freedom for and reward god-given talent, and the

important of talent-friendly legislation to attract it to these shores. But evidence

of genuinely portable, transformative talents are rare. Even in the cultural

industries where the uniqueness of talent is perhaps unparalleled, there are

profound limits to its effects when applied to new domains. Take a superstar

like Madonna for instance, despite an illustrious musical career her acting

career has earned her a record five Golden

Raspberry Awards; while retiring sports men and women notoriously struggle

to repeat their successes in other fields, often leading to feelings of social

dislocation and depression.

So let’s be more grown up about it. Talent is not fairy dust

and skill and expertise have a very specific context within which it is best

applied. That doesn’t discount the possibility that specialised skills can make

large differences in niche areas, which may justify large rewards. But that

then means we need some kind of activity or operating measure to gauge the

presence or absence of ‘talent’.

In banking arguably the most appropriate operating measure

of any banker’s skill is the return on assets figure: ‘how much net return can

you generate from the assets you purchase or create’? Here, the figures are

illuminating. The table below uses the 2011 results for Barclays (though we

could have used other years and other banks). It shows that in its capital

markets arm where the best paid bankers work, Barclays Capital, actually shows

a disappointing return on assets – lower than Barclaycard, their retail arm and

‘other’ activities. Furthermore it tells us something of the precariousness of the

monestised asset values from which elite bankers draw their high pay. Barclays

Capital makes more pre-tax income than any other segment and roughly 50% of the

group total, but it does so by stacking an astronomical £1.16 trillion of

assets onto the group balance sheet, which was 75% of the group total (and staggering

only a little less than UK GDP, which was £1.44 trillion in 2011). Here the

value of BarCap’s assets would need to fall a mere 0.25% to completely wipe out

the segment’s pre-tax profit; 0.5% to wipe out group profits; and 3.5% to wipe

out its profits and Core Tier 1 Capital (valued at £43,066m).

As we know, the value of these assets do fall and when they

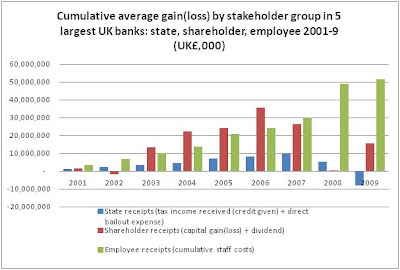

do, the repercussions for other stakeholders are dramatic. The table below

presents a stakeholder analysis of the top 6 UK banks from 2001-2009. It

presents the cumulative average gains for the state (tax income received and

direct bailout expense) for shareholders (capital gain/loss and dividends) and

for the workforce (staff costs) across the five institutions. The bailout figures do NOT include the

bailouts of Northern Rock (£25bn, 14 Sept 2007) and Bradford and Bingley (£42bn

29 Sept 2008); or emergency loans to HBOS & RBS October 2008 (totalling

£62bn); or special liquidity scheme/credit guarantee scheme (£500bn in total);

or asset guarantee scheme 24 Feb 2009 (£325bn). The shareholder figure is for

total capital gains/losses and dividend payouts and does not measure returns to

shareholders owning shares in 2001. So this figure, if anything, understates

the diverging fortunes of different stakeholders.

It would be difficult to credit those bankers at the heart

of the leveraged, CDO boom ‘talented’ by these graphs, even if they do have an

impressive record of educational attainment. In the same way that I would struggle

to justify the same term myself if, despite any apparent intelligence and

skill, I chose only to teach my students through the medium of mime and blew my

departmental budget on powerful hallucinogens which led me to perform demented shamanic

rituals on the ashes of my unmarked exam scripts. Talent must be recognised in

a particular context, and if the results disappoint then you have to raise

serious question about whether those skills are appropriate for that industry, whether

high pay is merited, and whether we should be thinking of these people as ‘talent’

at all.

If talent should be judged by performance, and performance

is disappointing, how do we explain the endurance of high pay norms then? It

may simply reflect two key industry features: i) the revenue earning capacity (NB

not profitability) of an industry or field and ii) the number of other charges

and claims on that revenue stream. The best paid UK academic will always

command a lower price than the best paid UK banker, not because the banker is

better in some market for abstract talent, but because a university has an

externally imposed revenue ceiling (student quotas, the resources available

from funding bodies etc) and a range of administrative, teaching and research

costs which mean claims on revenues are distributed amongst the many rather

than concentrated amongst the few. Similarly, a graduate with an engineering or

physics PhD will be differently remunerated depending on the industry in which

he or she chooses to work. Those skills may add equal value in manufacturing or

finance, but they will be more generously remunerated in finance because there are

a relatively smaller set of claims on that quantum of revenue. The central

claim of our 2006

book still stands: high pay is a function of position, not necessarily talent.

The real reason elite bankers are paid so much is because

they are a small group of interconnected individuals close to a big till.

This ‘big till’ and its attendant high pay norms are a dead

weight loss. A dead-weight loss refers to a situation where an

implied subsidy or some other distortion leads to an allocative inefficiency.

It is usually used by neo-classical economists to describe the distorting

effects of taxation, minimum wages etc on a free market. It has even been used

by bah-humbug-ers

to describe the net losses of gift-giving at Christmas. But here it could be

used to describe the effects of a bailout guarantee on the unit value of elite

labour. Bank bailouts have had two effects. First they have kept banks on life

support and allowed the continued payment of high fees to elite workers, when

by rights banks should be cutting costs and writing down debt. Second, with QE,

central banks have reduced the costs of capital to banks, allowing them to ramp

spreads on their outstanding and future loans – thus providing funds to both

recapitalise and maintain pay norms, while passing on costs to their customers

(as well as taxpayers and the public sector). This would not happen in any

other distressed business, where the workforce would immediately bear the brunt

of adjustment.

The big till is underwritten by government and central banks. But what are the social returns? The social dividend is limited by problems of insider claims and opportunity costs. On the former, for example, the generally accepted view of the mutual fund

industry is that actively managed funds pay more for their stock

pickers than those passive funds who simply buy the index, but that active

funds underperform passive funds (eg Gruber 1996). Further studies suggest that

net returns to investors are negatively correlated with a fund’s expense

levels, which are generally higher in actively managed funds (Carhart 1997). In

purely economic terms, this means that talent is overpaid on a marginal cost

basis: the skill of active stock pickers may allow the fund to generate superior

gross returns, but they incur higher costs from transactions, information and

pay, so that net returns to investors are lower. Put in the language of

‘claims’, this is the same as saying that any benefits which might accrue from

more accurate stock picking are captured almost entirely by insider talent

working within actively managed funds. The same may also be true of activities

like high-frequency trading which involve eye-watering sums spent on algorithm-builders,

code-writers and telecoms infrastructure which improve

latency by milliseconds and give traders manning the war machines of

finance fleeting advantages. Returns on individual trades may be marginally

higher, but those gains are largely claimed by insiders within the bank. Outcomes

for markets are as yet unclear

because it is open to all kinds of socially

useless wargaming, while returns to investors appear modest and may

disappear quickly. And, as Knight

Capital’s investors can attest, it may leave your capital exposed to

unforeseen software malfunctions and other unanticipated interactions in

complex systems – the likes of which Charles Perrow has

discussed.

If the higher returns that accrue from modest or superior

performance are captured by a small number of insiders, then we need also to

think about opportunity costs. That is – if those skills were applied to

another area of the economy, would they improve the national economy relatively?

If, rather than spending their time writing code for high frequency trading,

the same skilled engineers and mathematicians developed new software for high

tech manufacturing or green technologies or some other high skill, technology

intensive industry, would they produce more jobs, more spin-off activities,

more economic multipliers etc? I have no data or study to answer this question

(and it is a complex one because HFT clearly creates its own demand for

high-tech telecommunications investment), but my hunch is that on balance, they

may well do. Skilled workers would undoubtedly be paid less in other

non-finance industries, even if their net economic contribution were greater. Is

high pay in finance therefore more a market distortion rather than a sign of an

efficient market for talent?

It seems that the ‘market for talent’ metaphor is

inappropriate when explaining high pay in banking. Activity performance by any measure

has been poor, which suggests that whilst these individuals clearly have

skills, they cannot be considered ‘talent’ in many instances. Similarly high pay

is only possible because the industry is heavily subsidised and operates in a

permissive, lightly regulated environment. Their talent is not ‘bid up’ due to

its scarcity nor its transformative power. Even at the peak of the boom surveys

like that conducted by Deloitte found that only very small numbers of CFOs

within financial services claimed there was an ‘inadequate’ supply of talent

(defined as “high potential individuals likely to excel in finance”). With such

a thing in mind, perhaps the role of the banking institution is not to put a

ceiling on elite bankers pay, but rather to put an implicit floor under it by

sanctioning certain high risk, high volume, low return activities and creating

positions which allow a select few insiders to value skim for considerable

personal gain?

Stanley