In December, Adam Leaver and Daniel Tischer from the Alliance Manchester Business School hosted an international workshop on “Networks in Finance” at the University of Manchester. The event brought together both renowned and emerging scholars from different disciplines interested in net-work structures and dynamics within global finance. Despite the considerable diversity of approaches, the presentations shared the assumption that a focus on relationships can help us understand ongoing structural transformations like financialisation or the astonishing re-stabilisation of the industry and its guiding logics after the last financial crisis. “We can only really understand practices and outcomes of finance if we precisely know how it is put together and interconnected”, as Adam put it in his introductory remarks. Social network analysis (SNA) helps us a great deal in this respect since it enables the mapping of actor constellations over time and the connectedness of finance across sectors and borders. Throughout the workshop, three themes emerged: Firstly, the network characteristics in certain sectors of global finance; secondly, the connectedness and activities of particular actors; and finally, financial networks at particular places. This summary covers the various contributions along these themes rather than reporting them chronologically.

Networks in particular financial sectors: CDO, M&A, crowdfunding & CMU

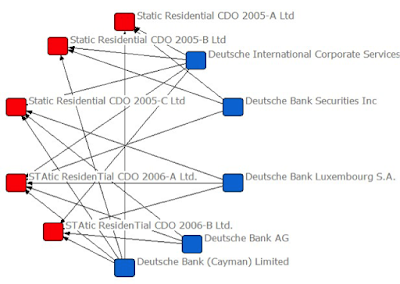

Finance is not a monolithic bloc although our use of this label sometimes might suggest this. It rather is comprised of a variety of sectors, markets, products, actors, and practices that share some common logics but can be structured quite differently. Thus, networks in finance might be best captured by looking at particular sectors. Adam Leaver and Daniel Tischer, for instance, showed how Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDO) are essentially networked products that emerge from a complex set of relations between different actors such as banks, legal advisors, collateral managers, and issuers. The global CDO industry can be analysed as a network that is generally concentrated in few actors and places but allows competition in some functional areas. The technical complexity and opaque-ness of the product serves as an exclusion mechanism and requires smooth, established and repeat-ed interactions between the actors involved. A network analysis of the supply-side of such markets questions the assumption of financial “bubbles” being mostly demand-driven. In their contribution on social network risk, they show how the quotidian careful consensus building among actors involved in the LIBOR fixing scandal as documented in leaked emails is another example of the importance of person-to-person relationships in finance. Not the corruption and misbehaviour part of the story is the most interesting bit but rather the habitual construction of the rules of the game by a close and tight network of insiders. In those constellations, often, common career patterns and alumni networks play a central role. Individuals and individual networks might matter much more in an industry that is often presented as anonymous and technical. And this might not only be the case for well-documented scandals but for the mundane practices within finance in general. This assumption is underpinned by Olivier Godechot´s presentation on team moves in the UK financial sector. Changing companies is happening quite regularly in finance, it maybe is even much more frequent than in other sectors. Godechot shows that also team moves are a significant phenomenon that is supported by specialised head hunting firms. The rationale behind this is keeping the clients and the established working proceedings within the team. Valerie Boussard showed, in the case of Mergers and Acquisition (M&A) services in France, those conventions about interaction and the organisation of transactions are key for the working of finance making it a “social field”. She finds a rise of inter-mediation services and reproduction of hierarchies among actors.

Andrew Leyshon presented a paper on the rather dynamic crowdfunding sector that puts the notion of networks at its core bringing together borrowers and lenders outside of the established financial markets. He questions the perception of crowdfunding being an alternative to mainstream finance. In spite of providing capital for projects that otherwise might not have been funded, it replicates many features of traditional finance like the class, gender, and geographical bias, the encouragement of entrepreneurship, and the reliance on transaction fees. Moreover, traditional actors infiltrate crowdfunding networks as lenders and experts. After all, like in other financial sectors, the most stupid (or least informed) person in the room ends up with the highest risk. Regarding capital markets, Ewald Engelen presented a paper (co-authored by Anna Glasmacher) on the European Commission´s attempt to set up a Capital Markets Union (CMU). He differentiates between a frontstage story presented by the Commission as rationale for CMU (bringing together capital demand and supply more efficiently) and what he identifies as backstage story of this policy, namely providing a new funding tool for big banks and saving securitisation. Thus, a narrative of financial modernisation serves as legitimation strategy for new politics of mass financialisation in the EU. Most interesting from a net-work perspective is the analysis of a contingent interest coalition behind this new regulation consist-ing of the Commission, banking associations, the ECB & the Bank of England, regulators, and institutional investors. This brings to the fore the pressing issue of the industry´s capacity to turn their interests into political projects promoted by state agencies which can be witnessed in various financial sectors and even after the recent crisis.

Relevant actors in financial networks: Organisations & individuals

Turning away from specific markets, another important question raised at the workshop concerned the nodes of networks in finance: Who are the important actors and brokers within those networks and how can we actually measure their influence? In technical terms, SNA measures importance by different degrees of centrality. However, this does not relieve us of the interpretation and theorising work that needs to be done in order to better understand the relationalities in finance and their functions. Sebastian Botzem presented a paper (co-authored by Natalia Besedovsky) that investigates the dynamic development of the global financial elite network drawing on a database including the big players of finance and their connections to other organisations via personal links. They interpret networks mainly as infrastructure for knowledge flows and find that the network becomes bigger and much denser over time and changes its face after the financial crisis. In particular, regulators, international organisations, and the industry itself lose connectivity while private non-profit organisations like think tanks and professional associations move towards the core. This might indicate an increased demand of sense-making, persuasion, and ideational self-assuring after the crisis and signals a renewal of the dominant self-regulatory pattern in financial governance. Jan Fichtner and Eelke Heemskerk also observe an interesting dynamic in the global network of corporate ownership: They trace back the rise of the three big passive index funds (Vanguard, Fidelity, Black Rock) and find that the crisis triggered an unprecedented shift of investment towards those funds that now represent the core of the network. What network analysis does not reveal, however, is how this translates into changes in corporate governance. Anecdotal evidence, however, suggests that index funds show a rather management friendly voting behaviour in shareholder meetings. Similar to the previous paper, SNA is rather limited when it comes to understanding reasons and implications of network change.

Coming back to the individual level, professional experts have been the focus of other workshop contributions. Ronan Palan stressed that asset managers essentially try to disproof the dominant theoretical underpinning of contemporary finance, namely the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EHM). They only can generate higher profits than their competitors if they beat the market (what EHM assumes to be impossible on the long run). Palan concludes that sabotage (operating outside the market) is the only way how higher income can be generated in this sector, making it the rule rather than the exception. In general, finance is a commission-based service economy that by default develops a behaviour that would be less tolerated in other businesses. Yuval Millo pays closer attention to positional struggles of investment advisors within financial networks. He finds that sell-side analysts try to accumulate social capital in order to respond to the increasing questioning of their legitimation. In particular, their reports turn from an informational into a relational device: They are no longer meant to provide knowledge but rather contacts. Thus, reports are written in a way that provokes the read-er and renders a personal meeting more likely. Similar networking efforts under pressure have been observed by David Muzio and James Falconbridge in the case of Italian lawyers who were getting ready to serve the newly financialised economy from the 1990s onwards. In order to keep up with both new legal requirements and Anglo-Saxon competitors, an emerging group of legal experts start-ed to internationalise their careers with Master degrees in New York or London and memberships in international professional associations. Finally, Rasmus Corlin presented joint research with Leonard Seabrooke and Duncan Wigan on professional competition in the governance of global wealth chains. He showed how different professional groups are struggling over influence on the OECD´s BEPS project. Experts who are either well-connected and experienced in different fields (“octopuses”) or who are focused and well-respected within their profession (“arrows”) succeeded.

Financial networks at particular places: The City of London and beyond

A third prominent theme at this workshop was the local dimension of financial networks. Arguably, all networks include places (mostly they are not bound to one place however). Still, in some studies, the local context is more focused on than in others. Those studies also tend to engage more with politics and financial regulation pointing to the fact that finance is essentially a political relation. Many academics are looking at relational and political dynamics at the City of the London. Sarah Hall, for instance analyses the emergence of London as first centre for trade in Chinese currency outside Asia. She argues that political decisions, social relations and power are key to the rise of certain places within global networks. The choice of London was not natural or business-driven but rather an outcome of favourable regulation, high level political contacts, and the reservations against New York. Jonathan Beaverstock presented some scenarios for the City post-Brexit and argued that the future approach to immigration will be crucial for its survival. This is based on the observation that international financial centres heavily compete for transnational labour. Places like Hong Kong and Singapore run quite aggressive global talent programmes and London will need to keep up in order to stay attractive for the transnational financial elite. This creates a challenge for policy-makers since special regulations for the capital are not likely to be popular in the UK.

Moving from London towards overseas tax havens, Richard Murphy suggests the term “secrecy juris-dictions” as new label for offshore financial centres. He argues that tax avoidance and evasion is en-abled through networks deliberately designed to provide secrecy spaces for foreign individuals and corporations. Those networks involve both public and private actors. However, the relations be-tween the actors might be much more important that the nodes themselves. Emmanuel Lazega and Chrystelle Richard looked at the networks of Public Private Partnerships (PPP) in France and showed how the state is an important facilitator of financialisation. The French PPP networks are characterised by a close relation between the state and big business, and by a centrality of banks and other financial actors who try to shift the risk towards the state. Finally, Sheri Markose showed that a net-work perspective can also help to shed light on current economic stagnation and high unemployment in certain US regions. If a production network loses connectivity, it also loses functionality. Also, fi-nance´s ever increasing share of GDP worsens the situation since all the oxygen in the room is sucked up by the financial sector. Therefore, the US economy needs to be rebalanced.

Merits, limits & methodological challenges of social network analysis in finance

In many but not in all workshop contributions, SNA was at the heart of the study, taking into account the various advantages of the network perspective. First and foremost, studying financial networks puts emphasis on agency and actors rather than treating finance as a merely technical, impersonal, and apolitical sphere. This includes awareness to conflicts, power dynamics, social and cultural norms. Network analysis also necessarily entails a process perspective regardless whether or not changes over time are studied. When we look at networks we are asking how exactly outcomes and practices unfold and which actors are involved in shaping them. This fits both the high complexity and dynamism of contemporary finance. While some authors started with the aim to map out a cer-tain networks, hoping to generate new empirical and theoretical insights, others simply decided to add the network perspective to their existing analysis in order to enhance their understanding. Both approaches are perfectly legitimate; their results, however, are not easily to compare.

Anyway, most of the papers combined SNA with other methods like content analyses of interviews and documents or sequence analyses of individual careers. Such triangulation seems to be quite promising since our interest usually does not stop after the mapping of networks. We want to under-stand the relations underpinning finance and their dynamic development. This clearly requires theorising since SNA is merely a descriptive tool. It is worth mentioning, however, that mapping a net-work can be a tricky task given methodological challenges like data availability, comprehensiveness, and reliability. Sources for network data include commercial corporate databases like ORBIS and BoardEx, annual reports, legal product descriptions, leaked communication (like emails), minutes, official registers, social media data (like Linked In and twitter profiles), public biographical information, and interview material. This data often is hard to gather and you rarely can be sure that you have complete information. Relatedly, the boundary question is anything but trivial: Where are the boundaries of a particular network to be drawn and how can this decision being justified? There was also some discussion about how much formalisation is necessary and desirable in the analysis of financial networks and whether more emphasis should be put on the nodes or the relations.

What do we already know and what needs to be investigated further?

The discussions in Manchester both showed how much we already know about networks in finance and revealed many gaps still to be filled. We know that networks, in finance and anywhere else, can be defined as rather small populations of frequently and repeatedly interacting people or organisations shaping outcome and reproducing shared assumptions or ideas. More specifically, networks can serve as infrastructure for power relations, control, knowledge flows, and product proliferation. We know that finance, as any other sphere of society, is constituted by and put into practice through networks. This is particularly true for the complex process of financialisation. Finance might even be inherently networked because it is an intermediary business. It is also to be assumed that networks in finance tend to be more transnational than other networks and that finance is exceptionally highly connected with other sectors (although there are only few comparative studies). What we don´t know exactly is how this connectivity and transnational character have evolved over time. Are con-temporary financial networks denser and more transnational than in previous times? The financialisation literature suggests an increasing connectivity but also a non-linear and variegated development. Which actors were central at certain periods of times? Are there historical patterns that span different financial sectors and regions or are the dynamics more context-specific?

We also know that financial networks develop very dynamically, maybe much more dynamic than other sectors. The reasons and implications of network changes, however, merit further attention. Why and how do certain actors become more central than others? Is it an outcome of deliberate strategies, power resources, or does it happen accidentally? How do networks react to shocks like financial crises? Some of the workshop contributions suggest they might change their form in order to keep their function. But is this true across the board? The workshop papers also suggest that there are considerable differences in the networks in different sectors and places. It is an empirical question whether networks in financialised capitalism tend to harmonise or can easily accommodates sectoral, cultural, or local particularities. One of the most important questions still needs to be investigated further, namely how do relations in financial networks unfold and how we can make sense of them. Maybe a theoretically informed typology of network relations could be helpful in this regard. Of particular interest are relations between public and private actors. How does the financial industry integrate state agencies in their networks and vice versa? How can explain the cognitive capture of regulators? Much more studies on regulatory networks are needed. We also might want to know how networks need to be changed in order to achieve substantial changes in finance and it´s regulation and how this can be achieved.

Conclusion: Towards a common research agenda?

Social network analysis enables the mapping of relations among financial actors and thereby generates a variety of new insights and triggers new questions. In particular, it makes visible hidden connections and changes over time. A network perspective certainly enhances our understanding of the inner workings of global finance. However, it certainly does not replace theorising relations and is more a descriptive than an explanatory tool. The workshop showed that the application of network research to the study of finance can produce much more than fancy network graphs. But it has to be connected with a critical analysis of power dynamics, expertise, and the social and political context of relations within finance in order to present an angle different from mainstream economics. In doing so, the research brought together in Manchester sheds new light on a still growing sector of society and its local and global interconnectedness. This event might lead to further collaborations among the participants. Certainly, it has reinforced an ongoing academic conversation on the important role of networks in finance. It might even have been a first step towards a much needed common re-search agenda on the networked character of global finance.

By Sebastian Moller, University of Bremen